There are few more devout lives in the set of all animals than a coral’s. In adulthood it surrenders swimming to settle on the sea depths, encompass its cowardly body with clones, and turn into a rock. Mouth confronting the sea, it sits tight latently for whatever floats by—or possibly not all that inactively.

Investigating these animals, researchers have found that corals utilize their little bodies to make swirling flows that are moderately tremendous. By constraining the sea water to move atoms closer or more distant away, they work to keep themselves alive.

On the off chance that you could scuba swoop down to a hard coral and zoom into a tiny perspective, you’d see the surface secured in the coral creatures’ minor hairs, called cilia. Numerous individuals have looked carefully at corals in the recent past, truth be told even Darwin examined coral reefs while on board the Beagle.

What’s more a few researchers have perceived that the waving cilia keep a slender layer of water moving parallel to the coral’s surface—like “a transport line,” says Orr Shapiro, a postdoc at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science who considered corals while he was a specialist at MIT.

This basic rinsing can help pull nourishment to a coral creature’s mouth or divert trash from the coral’s surface. At the same time past that, corals appeared to be helpless before sea ebbs and flows to bring them gasses and supplements that they require and to divert waste items.

Furthermore its not just their own particular needs that corals need to stress over. Most corals live with cooperative green growth in their tissues. They nourish and house the photosynthesizing cells, while in exchange the green growth utilize the sun’s vitality to give the corals carbon and help them assemble their stony dividers.

(Worried corals kick all their green growth without a moment’s delay, which we see as coral dying.) The corals need to sustain and clean up after their algal houseguests and additionally themselves.

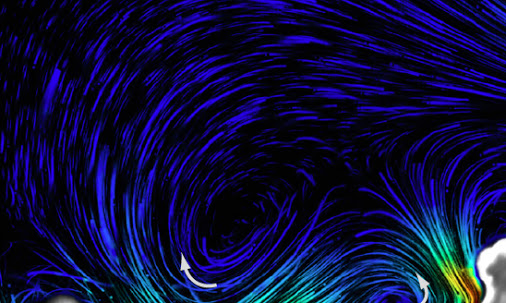

Shapiro and his coauthors looked additional carefully at corals—particularly, at a reef manufacturer called Pocillopora damicornis, or the cauliflower coral. They added tracer particles to the water around corals and utilized fast feature microscopy to watch how it streamed. What they saw was less like a transport line and more like a Van Gogh painting (as in the picture above).

The coral cilia were making swirling vertical whirlpools in the water. These vortices always turned against one another: “think about the turning cutting edges of a hand blender,” Shapiro says. Every vortex could extend a hundred or a thousand times higher than the length of the cilia.

On the scale of a coral, this adds up to just a few millimeters. In any case its sufficient to eagerly move the particles a coral needs to keep it agreeable. At the point when Shapiro measured the oxygen focuses around a coral, he saw that the vortices immediately conveyed oxygen-pressed water far from a coral (its algal companions can produce a perilous measure of the gas).

A numerical model uncovered that these vortices can accelerate the development of encompassing atoms by as much as 400%.

Shapiro doesn’t know beyond any doubt how regular this stealthy water swirling is among corals. At the same time in the wake of taking a gander at five other coral species and seeing the same vortices around every one of them, he supposes each reef-building coral may act thusly.

So why hasn’t anybody recognized before now? Shapiro says the sort of microscopy he utilized uncovered points of interest that past studies proved unable. Scientists had effectively watched the transport line stream above corals, however “being a bundle of designers” helped Shapiro and his coauthors understand the importance of the harder-to-see vortices, he says.

In the specialists’ numerical model, corals could make the egg-mixer vortices basically from every individual beating its cilia internal and outward. On the off chance that each individual does precisely the same thing, the bigger example develops no requirement for the coral creatures to facilitate with one another, scientifically talking.

Anyhow this doesn’t represent the transport line stream that additionally happens. Shapiro thinks the entire picture is more convoluted than his model, and that the yellow creatures may really be cooperating in some way or another. He trusts that breaking down the 3d structure of the stream may help answer this inquiry. Regardless of how the corals do it, however, their lives are obviously less calm than it seemed.